|

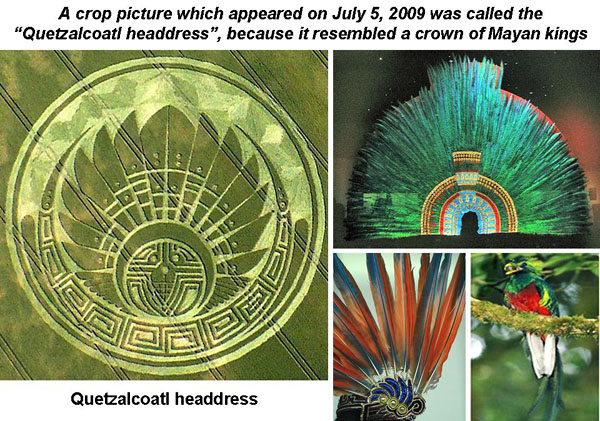

The “Quetzalcoatl headdress” of July 5, 2009 showed symbols from an ancient Mayan stela, to remind us that Quetzalcoatl ruled as a “king” on Earth during the seventh and eighth baktuns of our current Long Count calendar, or specifically from 33 BC to 191 AD A truly spectacular crop picture appeared near Silbury Hill in southern England on July 5, 2009 (see silburyhill2009 or lucy pringle or watch). It was quickly called the “Quetzalcoatl headdress”, because everyone could easily recognize that its primary symbol was a “quetzal feathered crown”, once worn by Mayan kings. A similar headdress was later worn by the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma, when the Spanish invaded his homeland in 1520 AD (see penacho or aztec-headdress):

Two other symbols for Quetzalcoatl as a “king” That crop picture also showed two other unmistakable symbols for the legendary Quetzalcoatl as a “plumed serpent” from ancient north America (see Awanyu), or as a “feathered serpent” from Teotihuacan in 200 AD (see Quetzalcoatl or silburyhill):

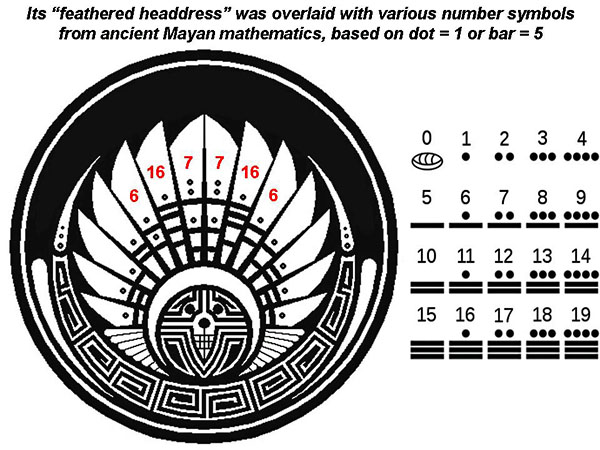

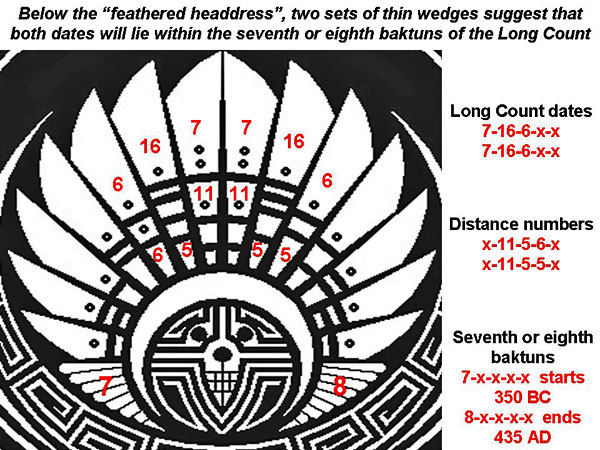

Ancient Mayan mathematics in modern-day England Its “feathered headdress” (showing seven large feathers on each side) was next overlaid with various number symbols from ancient Mayan mathematics, based on dot = 1 or bar = 5. A few of the uppermost numbers on either side may be tentatively assigned the values of 7, 16 or 6:

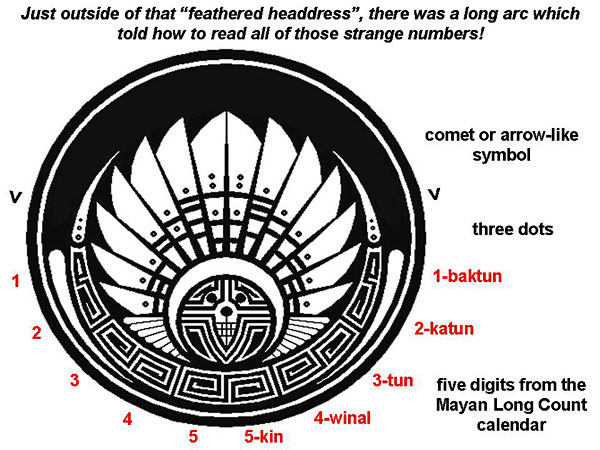

( In which logical context are we supposed to read those symbols? And what kind of message might they be providing us with? Come on, Quetzal, give us a little help! Instructions on how to read the message Well, he did give us some help, because just outside of the “feathered headdress” in the same crop picture, there is a “long arc” which tells us how to read all of those strange numbers! That long arc shows two comet or arrow-like symbols at the top on either side, each embedded with three dots. Then it shows five “square spiral” motifs which sometimes appear in Mayan-Aztec art, and seem to be associated with time-keeping or the calendar (see xochipilli-quetzalcoatl-aztec-calendar):

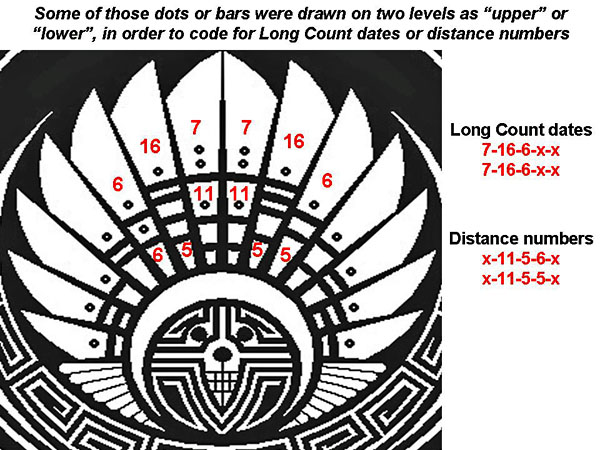

Square-spiral motifs have also been associated in modern crop pictures with the general concept of “calendar time”. For example at Wayland’s Smithy in August of 2005, they were used to denote a Mayan month of 20 days (see lucy pringle). Likewise at Silbury Hill in August of 2004, they were used to denote a Mayan 52-year Calendar Round (see lucy pringle). Here we are being shown five square-spiral motifs 1-2-3-4-5 for a crop picture that appeared on the matching date of July 5. Thus there would be an obvious tendency to associate them with five different units of time from the Mayan Long Count calendar, namely its (1) baktuns, (2) katuns, (3) tuns, (4) winals or (5) kins (see Mesoamerican_Long_Count_calendar). In summary, that long arc seems to be telling us: “Read those dots or bars from the ‘feathered headdress’ in terms of a Mayan Long Count calendar. Five successive digits 1-2-3-4-5 of any Long Count date may be read by going outward and down, on either left or right, starting from the uppermost pair of feathers at top”. There are of course seven large feathers on each side of the headdress, rather than five. Yet two additional dates were often added to the Long Count on Mayan stelas, from their Tzolkin or Haab calendars (see Maya_calendar or f-estela). Dots and bars on two separate levels: how to read? So yes, we seem to have been instructed on how to read those dots = 1 or bars = 5 from the “feathered headdress”, in terms of one or more ancient Mayan calendars. Such helpful instructions are not quite enough, however, because some of the dots or bars within each “feather” seem to have been drawn on two separate levels as either “upper” or “lower”. For example, we can tentatively assign values of 7, 16 and 6 to the first three upper-level “feathers” on each side, while we can tentatively assign values of 11, 5 and 6 to the first three lower-level “feathers” on the left, or 11, 5 and 5 to the first three lower-level “feathers” on the right:

What could this possibly mean? Two-part numbers could in principle stand for very large values in Mayan mathematics, for example 7/11 where 7 x 20 plus 11 = 151. Yet those large values would not make any sense in terms of a Mayan Long Count calendar, for which the biggest numbers should be 20 or 18. A more plausible hypothesis would therefore to be associate all of those dots and bars from each lower level with Mayan “distance numbers”. Mayan distance numbers and Long Count dates Distance numbers were often written alongside Long Count dates on ancient Mayan stelas, in order to specify the end of some important historical event or kingship, as well as its beginning. Thus any distance number could be added to a nearby Long Count date, in order to specify another Long Count date in the close or distant future (see sacred-texts or maya_astronomy or traditionalhighcultures). If this idea is correct, then we should be able to read two Long Count dates 7-16-6-x-x from each upper level of the “headdress” on left or right, plus two sets of distance numbers x-11-5-6-x or x-11-5-5-x from each lower level, again on left or right. And when we add those two sets of numbers together, we ought to find a second set of Long Count dates near 8-7-11-x-x or 200 years further ahead in the future (see pauahtun). Hence both sets of dates should lie within the seventh or eighth baktuns of our current Long Count calendar. The seventh Mayan baktun 7-x-x-x-x began in 350 BC, while the eighth baktun 8-x-x-x-x ended in 435 AD (see pauahtun). Another clue on how to read the message: seven or eight baktuns! Interestingly enough, the crop artist (in his infinite wisdom) seems to have given us yet another helpful clue that this interpretation may be correct, by drawing two sets of long, thin wedges slightly below the “feathered headdress” on either side. One can see there seven thin wedges on the left, or eight thin wedges on the right:

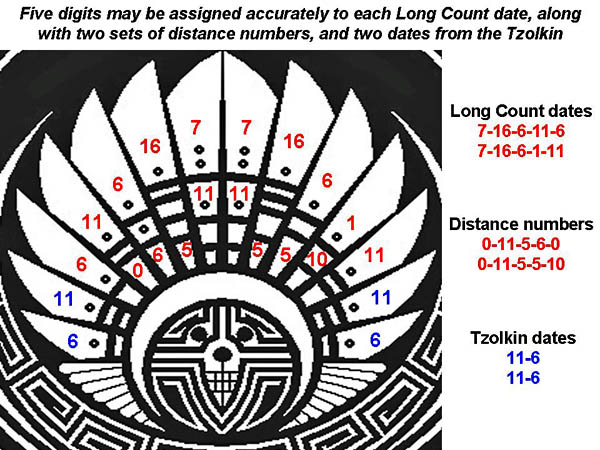

( Those two sets of wedges, seven or eight in number, would seem to suggest that Long Count dates from elsewhere in the “headdress” might begin with 7-x-x-x-x or 8-x-x-x-x as just derived above. Assigning all five digits to all four sets of numbers With these general concerns in mind, let us now try to assign precise and complete values to each Long Count date, or set of distance numbers, by careful inspection of the crop picture as shown. In some places, the complete reading of all five digits seemed ambiguous, so we used a program “Search for matching dates” (see pauahtun) to look for the best answer. We chose 7-16-6-x-6 or 7-16-6-x-11 for partial Long Count dates, and required each Long Count date to match the 11th day of some month from another Mayan calendar known as the “Tzolkin”. Two additional digits 11-6, which were drawn on either side below the fifth digit (6 or 11) of the Long Count, traditionally represent day-month dates from the Tzolkin in Mayan stelas or codices:

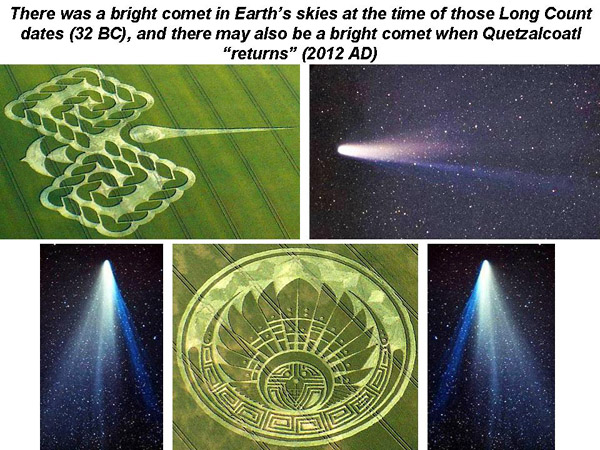

Using that program, we were able to plausibly assign two ambiguous digits x as follows: Right upper level > 7-16-6-1-11 = 11 Chuwen, month 11 of the Tzolkin = October 31, year -32 or 33 BC Left upper level > 7-16-6-11-6 = 11 Kimi, month 6 of the Tzolkin = May 14, year -31 or 32 BC The left-hand date lies slightly ahead in time of the right-hand date by 11-6 = 226 minus 1-11 = 31 or 195 days. Interestingly enough, the first three digits 7-16-6 from each of our Long Count dates match those carved onto one of the earliest known stelas in central America, from Tres Zapotes in 32 BC, which shows a Long Count date of 7-16-6-16-18 (see Tres_Zapotes). So far all of our calculations seem trustworthy and self-consistent, except for one small place on the right, where the Tzolkin date might be expected to be 11-11 (in accord with a fifth digit 11 of the Long Count) instead of 11-6 as drawn. Now let us try to assign two “distance numbers” from each lower level. Each of those distance numbers may then be added onto a Long Count date as just derived, in order to find two other Long Count dates further ahead in the future: Right lower level > a distance number 0-11-5-5-10 may be added onto 7-16-6-1-11 to yield a future date of 8-7-11-7-1 = November 26, 190 AD (1 Imix-1 or first day-month of the Tzolkin) Left lower level > a distance number 0-11-5-6-0 may be added onto 7-16-6-11-6 to yield a future date of 8-7-11-17-6 = June 19, 191 AD (11 Kimi-6 or same day-month of the Tzolkin). The left-hand date lies slightly ahead in time of the right-hand date by 17-6 = 346 minus 7-1 = 141 or 205 days. Four Long Count dates from 33 BC to 191 AD: the reign of Quetzalcoatl? By a careful study of Mayan number symbols in the “headdress”, we have thus been able to find four Long Count dates which begin in October 33 BC or May 32 BC, and end in November 190 AD or June 191 AD. What could those dates mean in a historical sense? Some of the earliest stelas from central America were erected in 36 or 32 BC (see Tres_Zapotes), while the famous Temple of Quetzalcoatl in Teotihuacan was not completed until 150 or 200 AD (see Temple_of_the_Feathered_Serpent,_Teotihuacan). Indeed, why was this amazing crop picture sent to us on July 5, 2009 in a field near Silbury Hill? Could it have been meant to remind us of an overall period of time when Quetzalcoatl ruled as a “king” in ancient central America, around the time of Christ from 33 BC to 191 AD? Is that why it showed a “quetzal feathered headdress”, once worn by Mayan kings? And why it showed two other symbols for Quetzalcoatl as a “plumed serpent” or “feathered serpent”? Cometary symbolisms: a bright comet flew through Earth’s skies in 32 BC If so, then what about its many cometary symbolisms? Four comet-like symbols were drawn around the central “headdress”, proceeding either up or down on left or right:

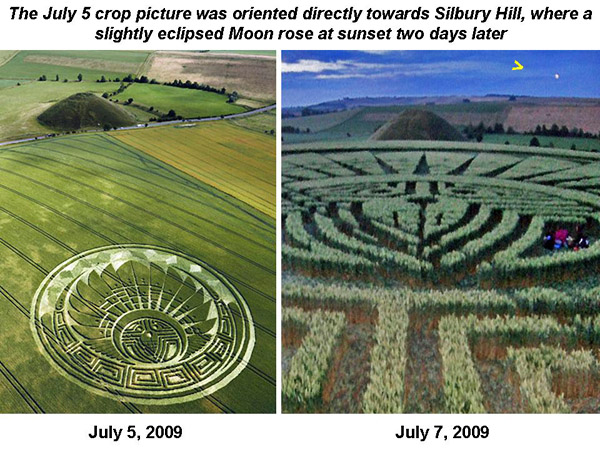

Well, the Mayans would often erect stelas to mark significant astronomical events (see mesoamerica or dartmouth.edu). Historically, we know that there was a bright comet in Earth’s skies during February of 32 BC, midway between the first two Long Count dates of October 33 BC or May 32 BC (see what-and-when-was-star-of-bethlehem-was). Likewise, there was a bright comet in Earth’s skies during 185 AD, just five years before the second two Long Count dates of November 190 or June 191 AD (see “Identification of the guest star of 185 AD as a comet”, Nature 371, 398, 1994). More recently, several crop pictures have seemed to suggest that a bright comet may appear in late 2012 when the Long Count calendar ends (see WHAT DO MODERN CROP PICTURES MEAN). Field orientation towards a penumbral lunar eclipse on July 7, 2009 Now when that “Quetzalcoatl headdress” crop picture appeared near Silbury Hill on July 5, 2009, there was no bright comet “flying like a swallow” through Earth’s skies (see lucy pringle). Yet two days later on July 7, there was a penumbral lunar eclipse! Indeed, the entire crop picture was carefully oriented so that an eclipsed Moon would rise at sunset behind Silbury Hill, as seen by anyone standing in the flattened crop:

That crop picture even showed in its lower part two large symbols for “eclipse” or “sextant”, along with “four broad arrows”, to tell everyone where to look for an eciipsed Moon (see on the left above). The “owl” as a symbol for “Tlaloc”, another Mayan god Did any other crop pictures from 2009 show symbols from ancient Mayan culture? Well, an "owl" which was drawn in crops on August 10, 2009 (see woodboroughhill2009b) may have been intended to symbolize the Mayan god “Tlaloc”. Very similar Images were carved onto facades of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan in 200 AD, directly next to images of the Feathered Serpent (see teotihuacan or temple_quetzalcoatl). Detailed images of Quetzalcoatl from 2000 years ago Finally, how did the Olmecs or Mayans of ancient central America regard Quetzalcoatl 2000 years ago? Only two good sculptures remain from that time, and both portray Quetzal as a white-skinned man of European appearance:

On the left above, he is shown wearing his three-lobed jester’s hat, which has appeared in modern crop pictures many times, for example in East Field on July 28, 2006 (see lucy pringle). Then on the right above, he is portrayed as some kind of airman or astronaut, riding around within a “flying snake”. Could that be where the term “feathered serpent” comes from? A jump through time into our modern era? What might all of this mean? Let us suppose that an advanced group of human-like extra-terrestrials landed on Earth 2000 years ago, then settled in central America where they taught the locals everything they knew about calendars, astronomy, architecture, farming or religion. That scenario seems quite plausible, given the huge size of pyramids found later at Teotihuacan, or the high mathematical level of their calendar systems. They even told in one crop picture which star they came from (see time2007o). Yet why are receiving spacetime transmissions from them today, in the form of English crop pictures (see time2007e or time2007k)? Why did some of them visit Wiltshire last summer in order to inspect a great crop picture, called the “Quetzalcoatl headdress”, which they had just made (see telegraph.co.uk or colinandrews.net)? Their home city of Teotihuacan was literally deserted by 700 AD, as if all of its inhabitants had suddenly disappeared. Might some of those visiting extra-terrestrials, whom the Mayans knew as teachers or gods, be planning to jump through time into our modern era? Or have they already done so, and are just waiting to land? CMM Research P.S. We would like to thank Steve Alexander, Robert Armstrong, Zef Damen and Jack Roderick for some of the photographs used here. Appendix. Notes to explain the three most commonly-used Mayan calendars A typical Mayan calendar date looks like this: 12.18.16.2.6, 3 Cimi, 4 Zotz.

The Long Count is a mixed base-20/base-18 representation of five consecutive numbers A.B.C.D.E. When added together, those numbers represent the total number of days that have passed since the start of our current Mayan era or “Sun” in 3114 BC. Each digit may vary individually as A (0 to 13), B (0 to 20), C (0 to 20), D (0 to 18) or E (0 to 20). The total number of days which may be encoded by each digit equals (see Mesoamerican_Long_Count_calendar: E = 20 D = (18 x E) = 360 C = (20 x D) = 7200 B = (20 x C) = 144,000 A = (13 x B) = 1,872,000 Why was such a strange calendar ever invented? Perhaps to help the Mayans or Olmecs count long periods of time on their fingers using integers, without requiring the use of modern decimal fractions! The overall length of any Mayan Sun in this calendar is 1,872,000 days, which equals 5200 “years” of 360 days, or 5125.36 solar years of 365.24 days. Our current Mayan era or “Sun” began on August 13, -3113 (or 3114 BC), which equals 0.0.0.0.0 in the Long Count, or alternatively 4 Ahau, 8 Kumku in the Tzolkin and Haab. Our current era will end on December 23, 2012 AD, which equals 13.0.0.0.0 in the Long Count, or alternatively 4 Ahau, 3 Kankin in the Tzolkin and Haab (see pauahtun.org). The Mayans or Olmecs began to use a Long Count calendar around 36 BC, after a great and mysterious god-teacher known as “Quetzalcoatl” arrived on their shores by boat in the Yucatan. Some scholars have suggested that the first actively-kept Long Count date was 7.13.0.0.0 or September 12, 98 BC. Yet the oldest known standing stones or “stelas” show dates of just 7.16.3.2.13 to 7.16.6.16.18, equal to 36 or 32 BC (see calendar-mayan or sacred-texts.com). The Tzolkin calendar was specified by a listing of 13 days, numbered from 1 to 13, in combination with a “named month” of 20 days. The names and numbers of those Tzolkin months were (see Maya_calendar):

Both the day-number and the month-number would advance by one unit every day. For example, if today were 3 Cimi-6, then tomorrow would be 4 Manik-7, while the next day would be 5 Lamat-8. Another Tzolkin date of 3 Cimi would not arrive until a further 13 x 20 = 260 days had passed. There are 20 month-numbers in the Tzolkin, while the last digit “E” of any Long Count also contains 20 days. Furthermore, both calendars began on the same day of August 13 in 3114 BC. So the month-number of the Tzolkin should always match the last digit of the Long Count! For example, if today is Ahau-0 in the Tzolkin, then the last digit of the Long Count will be 0. Or if today is Cimi-6 in the Tzolkin, then the last digit of the Long Count will be 6. The Haab calendar consisted of 18 months of 20 days, followed by another 5 days to complete one 365-day solar year. The days of each month were numbered from 0 to 19, while the names of each Haab month were:

In contrast to the Tzolkin, month-numbers in the Haab changed only after any complete month of 20 days. For example, the Haab day after 4 Zotz would be 5 Zotz, followed by 6 Zotz, proceeding up to 19 Zotz, then switching to 0 Tzec. The Haab is thus more like our modern calendar than either the Long Count or the Tzolkin. Now in addition to the Long Count, Tzolkin and Haab, the ancient Mayans kept another measure of long-term time known as the “Calendar Round”, which lasted for 52 years. How did they arrive at a precise period of 52 years? Well, any Tzolkin year lasts for 13 x 20 = 260 days, while any Haab year lasts for (18 x 20) + 5 = 365 days. And the smallest number that can be divided evenly by both 260 and 365 is 18,980, equal to 52 years (almost). To be precise, 73 x 260 = 18,980 days for the Tzolkin, or 52 x 365 = 18,980 days for the Haab, while there are 18,993 days in 52 solar years. During those extra 13 days, once every 52 years, the Aztecs would hold a “New Fire” festival like our New Year’s Day (see New_Fire_ceremony). Their Calendar Round also had a direct astronomical significance, regarding the visible appearances of bright Venus as seen from Earth. Here is how it worked: any single cycle of Venus about the Sun requires 584 days (as seen from Earth), so 32.5 cycles of Venus will require 18,980 days. Thus by watching planet Venus appear in the morning sky then in the evening sky, 32.5 times in succession (see El_Caracol,_Chichen_Itza), the ancient Mayans could count 52 solar years quite precisely, so long as they added 13 extra days at the end to eat and drink and take a big holiday! After learning about all of these amazing calendrical and/or mathematical achievements from ancient central America, around the time of Christ, when most people in Europe could barely count on their fingers, we received the unmistakable impression that those three calendars (the Long Count, Tzolkin and Haab) could only have been taught to the natives there by a great genius: whether from somewhere else on Earth, or from the distant stars. How can we know so much today about those ancient Mayan calendars, if over-zealous Spanish priests burned most of their paper records or codices (see Maya_codices) as “works of the Devil”? Well, fortunately for us, the Mayans also erected many carved standing stones or “stelas” to record the beginnings and ends of kingships, or to commemorate important cultural or astronomical events. Such stelas have persisted quite readably in ancient Mayan ruins today, and often show all three calendars in the following order: five Long Count dates A.B.C.D.E on top, followed by two Tzolkin and/or Haab day-month dates in the middle, followed by one “Lord of the Night” date below, which is just a rolling series of numbers from 1 to 9 (see meso_astro). The two earliest known Mayan stelas show Long Count dates that begin with 7.16.x.x.x in 36 to 32 BC (see Tres_Zapotes or www.dartmouth.edu or Estela_C_de_Tres_Zapotes):

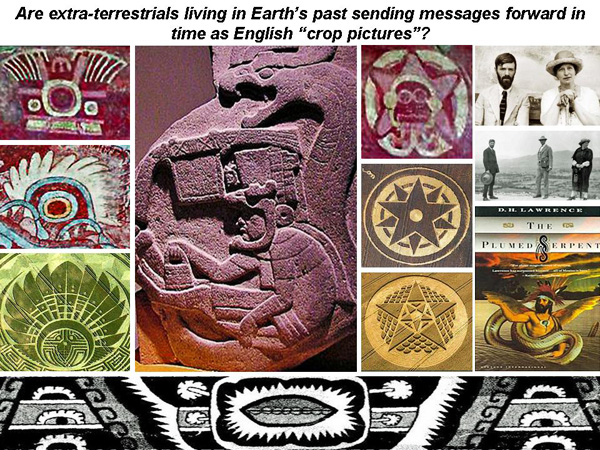

Appendix 2. True images of Quetzalcoatl and his headdress from ancient central America: could a small group of extra-terrestrials, living in Earth’s past, be sending messages forward in time to our modern era as English crop pictures?

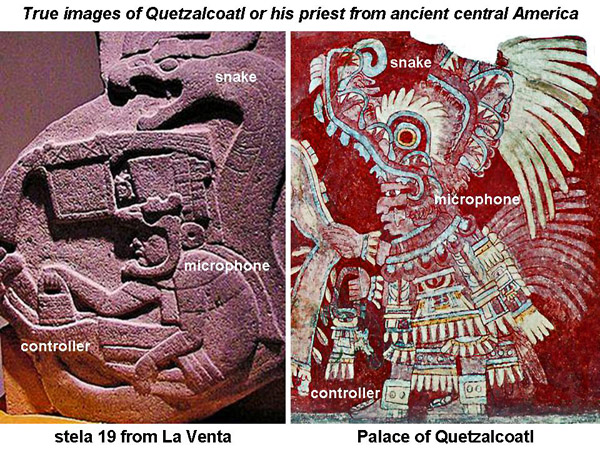

This slide shows at its centre Stela 19 from La Venta, which is the earliest known representation of a Feathered Serpent in central America. On the left it shows two quetzal feathered headdresses from the ancient Mayan city of Teotihuacan, along with a matching crop picture from southern England on July 5, 2009. On the right it shows a Venus symbol from Teotihuacan, along with two matching crop pictures from southern England on July 10, 1998 or August 26, 2002. On the far right it shows D.H. Lawrence visiting Teotihuacan in 1923, along with a cover of his book “The Plumed Serpent”. Finally at the bottom, it shows an ancient mural from Zacuala in Teotihuacan, which portrays a glowing saucer emitting four mushroom-like exhaust plumes, while two nearby “eyes” suggest that local people are watching. In the previous part of this article, we analysed mathematically a series of “dot = 1” or “bar = 5” symbols within the “feathered headdress” part of a spectacular crop picture which appeared near Silbury Hill on July 5, 2009 (see silburyhill2009 or www.youtube.com). Those Mayan numbers provided dates within their Long Count calendar which ranged from 33 BC to 191 AD by our modern calendar system. Quite plausibly, such dates could mark the beginning and end of Quetzalcoatl’s reign as a king in early central America, especially since the “feathered headdress” was one of his regal symbols (see time2010f). Here we will compare some of those modern crop-based images with true archaeological images of Quetzalcoatl or his headdress from ancient central America. Some of the images were taken from travel sites, for example Teotihuacan or www.richard-seaman.com, while more general information about the remarkable Mayan city of Teotihuacan may be found on www.world-mysteries.com. Early portrayals of Quetzalcoatl in central American art According to our previous findings, Quetzalcoatl may have ruled as a “king” in early central America from around 33 BC to 191 AD, while residing in his Palace of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan (not far from modern-day Mexico City). Murals or sculptures devoted to him literally cover that ancient temple, and provide much useful information concerning Quetzalcoatl as a person, and how he is portrayed in modern crop pictures. He was first portrayed in ancient central American art as shown below on the left, by a small statuette called “stela 19” found at La Venta in the Yucatan (see La_Venta or Olmec_religion). There we can see a man of European appearance riding inside of a “feathered serpent”, while wearing a modern airman’s or astronaut’s suit, a helmet with a small “microphone” curving around his neck, and holding some kind of “controller” device in his right hand. Behind him, we can see what looks like a modern flat-screen TV, along with several vertical rows of switches:

This is truly an out-of-place, out-of-time artefact, which should have suggested to Mayan scholars that something unusual may once have occurred in ancient central America! Next on the right above, we can see how some of the priests from his Palace of Quetzalcoatl later copied his attire in a kind of cargo-cult fashion: by wearing a feathered headdress with a long “snake” on their heads, wrapping a “microphone” around their necks, and holding a small feathered bag as the “controller” device. The broad, diffuse shapes shown emerging from the priest’s mouth are “speech bubbles”, just like we use in modern comic strips to indicate that someone is talking, although we do not know how to decipher those lost scripts. A remarkable crop picture appears near Silbury Hill on July 5, 2009 Now on July 5, 2009, certain unknown parties created a large and spectacular crop picture next to Silbury Hill in southern England, while several filmmakers were watching carefully with their eyes and cameras all of the night before, and saw no one in the fields below, until the Sun rose at 4:30 AM and a newly formed crop picture slowly became visible (see www.earthfiles.com or www.earthfiles.com). There were also rumours of three tall, blond extra-terrestrials of human-like appearance being seen in that crop picture by a Wiltshire policeman just after it appeared (see www.earthfiles.com or UFO-alert-police-officer-sees-aliens-at-crop-circle or /UFO-PoliceSergeant-SilburyHil). A lot of activity if nothing paranormal were really happening! The 7-7 feathered headdress symbolizes Quetzalcoatl as a king That remarkable crop picture is shown in the lower part of the diagram below:

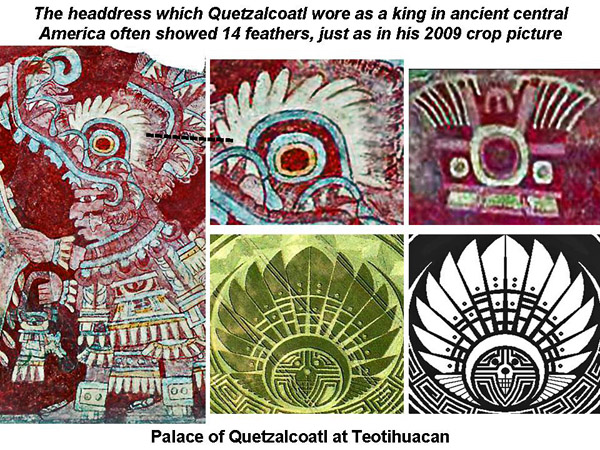

On each side of the centre we can count 7 “quetzal feathers”, whether on the left or on the right, to give 14 “feathers” in total. How might that compare with the real feathered headdress which Quetzalcoatl once wore as a king in ancient central America? Well, we can see on the left above one of his priests, wearing a white headdress with 14 quetzal feathers (or sometimes 15 in other murals). Then on the right above, we can see one of the many “feathered headdress” symbols which adorn the walls of his Palace at Teotihuacan. It shows 7 quetzal feathers on the left, and another 7 quetzal feathers on the right, to give 14 feathers in total (just as in the July 5 crop picture). Thus in summary, there seems to be an excellent match between what was shown in a field near Silbury Hill on July 5, 2009, and what appears in authentic archaeological records from ancient central America. A five-pointed star for planet Venus symbolizes Quetzalcoatl as a teacher of astronomy Now Quetzalcoatl was known not only for his distinctive “feathered headdress”, containing 7 quetzal feathers on each side. He was known also for a “five pointed star” which symbolizes planet Venus, because he taught the local Mayans and Olmecs all about Venusian astronomy, and even incorporated Venusian astronomy into their 52-year Calendar Round:

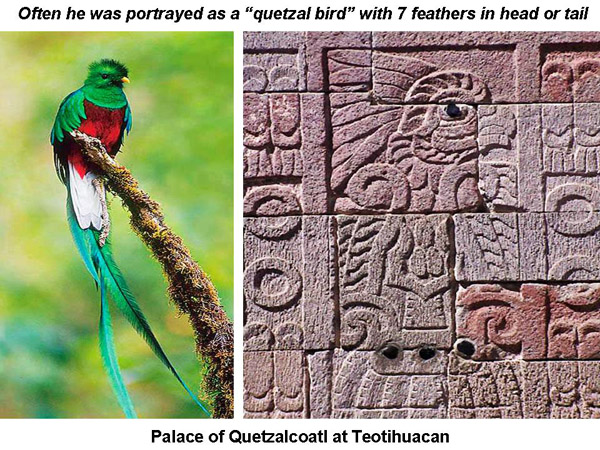

Such five-pointed stars have appeared many times in English crop pictures: for example on July 10, 1998 at Buckinghamshire as shown, or in other places (see time2007c or time2007e). A quetzal bird with seven feathers Likewise on various stone pillars at the Palace of Quetzalcoatl, he was portrayed as a “quetzal bird” with 7 feathers in his head, and 7 feathers in his tail:

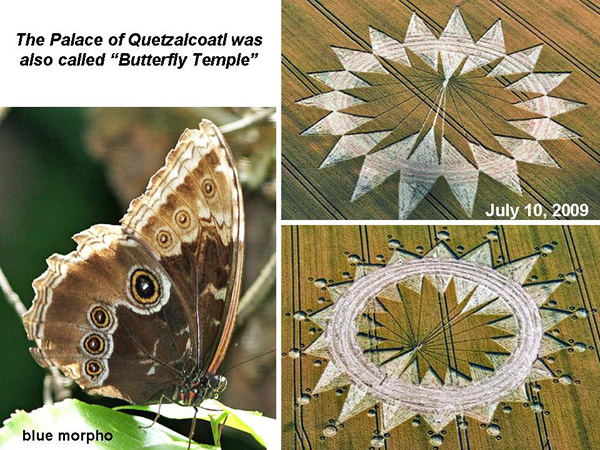

A butterfly with seven spots on each wing Indeed, his palace was sometimes called the “Butterfly Temple”, because many carvings of birds or butterflies adorn its stone pillars and walls! On July 10, 2009, just five days after that “feathered headdress” crop picture appeared near Silbury Hill, we saw a magnificent “butterfly” crop picture appear over two days at Cannings Cross (see canningscross2009):

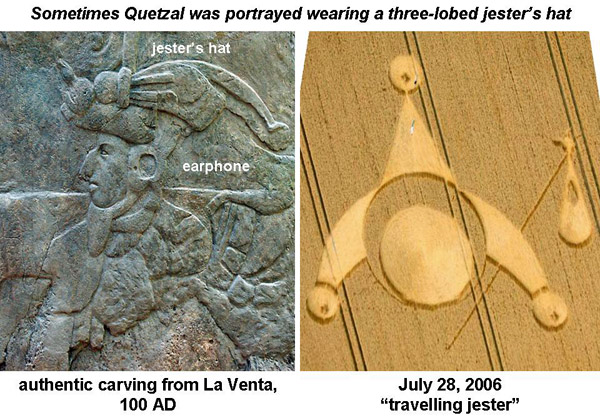

That “butterfly” crop picture shows “7 spikes” on each side to symbolize Quetzalcoatl’s headdress, plus 18 other spikes along the outside to symbolize his Long Count calendar. There is a beautiful butterfly native to central or south American rainforests called the “blue morpho”, which likewise shows seven spots on each of its wings. Despite being sent across thousands of years of spacetime, to remind us of Quetzalcoatl and his Butterfly Temple, that “butterfly” crop picture was quickly destroyed by a local farmer who had no concept whatsoever of its significance or its beauty. While we do need to respect the property rights of local farmers, when a new crop picture appears on their land, one can only recall here the words of another great spiritual teacher in the Middle East, who was teaching there on Earth at the same time that Quetzalcoatl was teaching in central America: “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.” A new interpretation for the “7-7” crop pictures of 2009 In light of this new research, the most likely meaning of many “7-7” crop pictures from last summer could be in terms of Quetzalcoatl’s feathered headdress, rather than a date of July 7, 2009 as was supposed at the time. It was tempting to associate those “7-7” symbols with “month 7, day 7” of the year 2009, because two other major crop pictures had appeared on dates of 7-7-2007 or 8-8-2008. Yet in retrospect, after doing further research, an alternative interpretation can plausibly be made. Should we fear the return of Quetzalcoatl as Stephen Hawking seems to suggest? Should we be afraid of Quetzalcoatl if he does return in late 2012? Stephen Hawking tells us that we should be “afraid of alien contact”, because Columbus, Cortes and other early Spanish explorers literally devastated all of the native cultures that they encountered in the Caribbean or central America (see technology_and_science-space). Yet is he making a valid analogy here? The very reason why Emperor Moctezuma allowed Cortes and his Spanish renegades to proceed freely through the Aztec empire in 1519 (see Moctezuma_II) was because of a case of mistaken identity. Moctezuma and his fellow Aztecs believed (at first) that the legendary Quetzalcoatl had finally returned to their shores, to bring them again an era of peace and prosperity. When he left “for the heavens” many hundreds of years earlier, Quetzalcoatl had promised that he and his friends and family would one day return: “Cortes was unaware of the spiritual implications that surrounded his expedition. His arrival in the Americas coincided with the predicted return of a Plumed Serpent named Quetzalcoatl, who was credited with teaching the use of metals and cultivation of the land. The expectation among ordinary Aztecs for the return of Quetzalcoatl was considerable” (see www.pbs.org) “In his letters to King Charles V of Spain, Cortés claimed to have learned that he was considered by the Aztecs to be either an emissary of the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, or perhaps Quetzalcoatl himself” (see Cort) Thus believing Cortes to be their long-lost friend Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma allowed those Spanish explorers into his capital city, where they soon took him captive and killed him, then destroyed the city (see Fall_of_Tenochtitlan). The three-lobed jester’s hat symbolizes Quetzalcoatl as a humorous joker But what about the real Quetzalcoatl, who built a great city at Teotihuacan, taught mathematics and calendar systems, and built the Butterfly Temple? What was he like as a man, or as a human-like man coming from the distant stars? As far as we can tell, the local people viewed him with gratitude for bringing them prosperity in all aspects of life. The Hopis for example called him “Pahana” meaning “lost white brother” (see Pahana). Yet they also seemed to have viewed him with a certain kind of amusement. For example, he was often portrayed as wearing a three-lobed jester’s hat, which later became the crown of Mayan kings (see jestergod). In the diagram below, we can see Quetzal at La Venta around the time of Christ, wearing his jester’s hat, and having a small listening device or “earphone” covering his left ear:

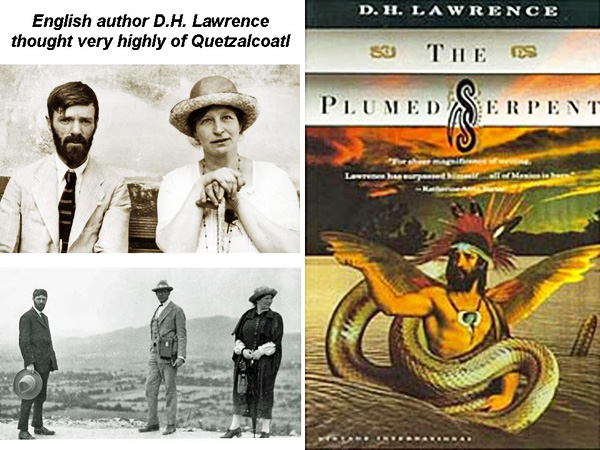

The “jester’s hat” motif has appeared many times in English crop pictures, for example at East Field on July 28, 2006 (see above right). There Quetzal cleverly added another symbol to his jester’s hat, namely a “hobo’s bag”, to indicate that he is now a “travelling jester”! He is indeed a long way from home. His home star lies 160 light years away from Earth in the constellation Hercules (see time2007o). And soon perhaps, he may travel once again through time to meet us in late 2012. D.H. Lawrence was fascinated by Quetzalcoatl In complete contrast to Stephen Hawking, the famous English author D.H. Lawrence found legends of the Plumed Serpent to be so inspiring, that he wrote a full-length book about them in 1925 (see mexicolore):

If Quetzal was good enough for D.H. Lawrence, then he may be good enough for us! The new 2010 crop circle season is just about to begin, so we will probably see more Mayan-type crop pictures appearing soon, sent to us perhaps from the Butterfly Temple in ancient central America? CMM Research

P.S. A small

“Roswell stone” was found in 2005 amid the mountains of New Mexico,

and shows a crop picture from England 1996 on one of its flat

surfaces. That strange evidence would seem consistent with some kind

of time-messaging hypothesis. The stone could have been carried from

Teotihuacan to New Mexico 2000 years ago, by one of the local

Anasazi tribes who would often trade with Mayans to the south. The

Olmecs were some of the first people on Earth to use lodestones for

navigation, and that rock was magnetic. Julian Gibsone flew to New

Mexico to investigate the “Roswell stone”, and his story may be

viewed at

/circles-hidden-mysteries. |